The Irish Times went to Rwanda and Nigeria with Bono and his One Foundation.

|

| At a solar array in Rwanda |

"Wonk and sizzle.” That’s Roxy Philson’s phrase to explain her organisation’s working method. Their goal is nothing short of mobilising the resources of the northern half of the planet to help the southern half. They want to engineer a tectonic shift in rich “us” and our responsibilities to help poor “them”, while simultaneously empowering “them”, so they can say goodbye to aid handed down from above.

It’s not an easy ask. But sizzle helps.

“Wonk and sizzle,” says Philson, who is chief marketing officer of the advocacy organisation One. “It’s what we do.”

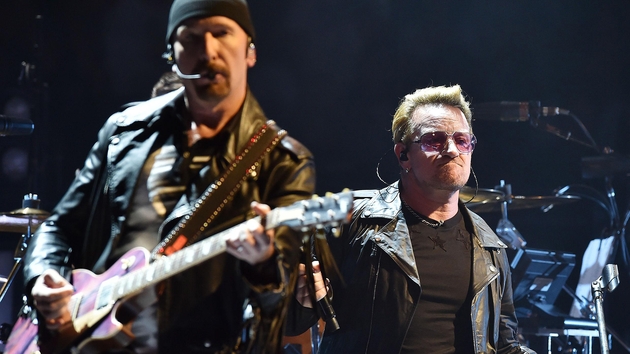

Bono, of U2, expresses it another way. “We like to get stuff done,” he says.

Getting stuff done in this project involves boning up on vast quantities of data – the evidence to back up your argument – and then using one’s celeb status to mix it with world leaders and the rich, many of whom are not on the Christmas card list of your average developing-world activist.

The activists, the people who know instinctively there’s something imbalanced and morally wrong with global inequality and want to change that, may or may not like U2’s music. They may blanch every time Bono pops up on the cover of Time magazine or on CNN, or is pictured smiling and joking while hanging out with the Clintons or Angela Merkel or David Cameron. Or even Vladimir Putin.

“Sell-out”, say his detractors. “Another rich guy”, “a wannabe member of the elite”.

But Bono is nothing if not pragmatic: he has one eye focused on the goal – debt relief, or beating Aids, or ending extreme poverty in Africa – the other on how you actually put the ball in back of the net, as opposed to insisting that a goal must be scored.

|

| Bono meets Hope , a patient at University Teaching Hospital in Kigali |

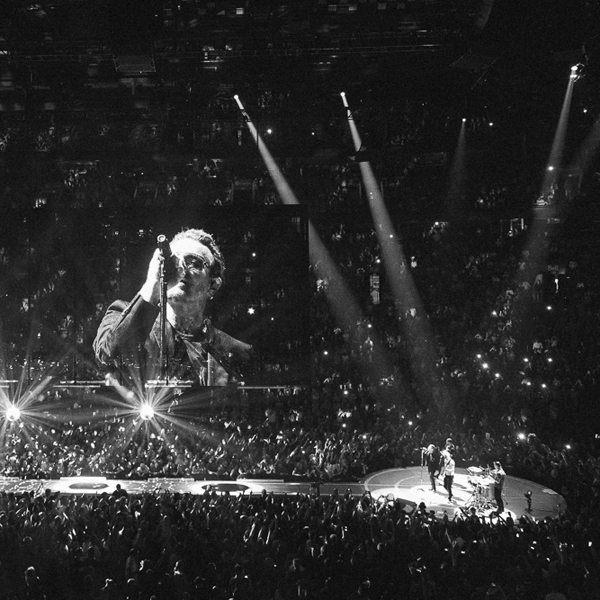

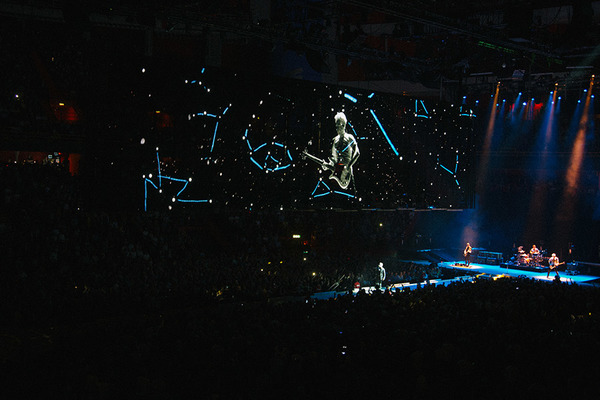

Monday August 24th: Pisa, Italy

Bono, fresh from the end of U2’s US tour, and with a week to spare before rehearsals for last night’s Turin opener of the band’s European leg, steps into the jet he has personally paid to charter, to take him and part of the One team to Rwanda and Nigeria.

He is greeted warmly by the captain, copilot and two cabin crew, for whom Bono, even among their other high-end clients, comes with a very big wow factor.

He walks down the inside of the plane to where the rest of us are sunk into vast leather armchairs that tilt back into beds. We are cocooned in a gleaming, polished cream interior comprising five connected but well-defined spaces.

Bono stops and raises both arms in front of him, palms turned open, fingers splayed, gesturing to the vista of opulence before him. “Ain’t never been on one of these before,” he says, grinning from ear to ear.

Even for a group of moneyed philanthropists this kind of transport is not par for the course. The larger-than-usual plane is being used because of the size of the delegation making the five-day trip to Rwanda and Nigeria.

In Rwanda the aim is to see what has been achieved there with money raised by , founded by Bono and others, that partners with corporations, such as Apple, Bank of America and Starbucks, and has so far raised almost €290 million. The money has been given, without any deductions, to the Global Fund, the Geneva-based not-for-profit organisation with close ties to several UN agencies, including the World Health Organisation (but which is part of neither). Ireland contributed €163 million to the fund between 2001 and 2013.

The fund raises money from governments, civil society and the private sector to fight Aids, malaria and TB and deals with recipient governments, agreeing programmes, monitoring spending, assessing outcomes. The fund has spent more than €700 million in Rwanda, of which €70 million came from (Red). Most of the €700 million, and all of the €70 million, has been spent fighting Aids.

The trip is for the benefit of significant private-sector partners of One, some travelling with Bono, some already in Rwanda, and key personnel within One and (Red). In Kigali, the Rwandan capital, the delegation will hook up with a bipartisan US congressional delegation making a separate tour of several African countries.

After Rwanda it’s west across the continent to Lagos, in Nigeria, where One is using pop music to build a bottom-up citizens’ campaign for radical change, focused at the moment on women as part of the sub-Saharan-wide Poverty Is Sexist campaign.

The delegation travelling down with Bono includes Tom Freston, the MTV founder and ViceNews board member, who is also chairman of One; Mario Batali, a New York celebrity chef; Anne Finucane, vice-chairman of the Bank of America, who oversees dispersal of the bank’s €9 billion charitable foundation (€9 million of which has been committed to One via (Red); and Douglas Alexander, a former British Labour Party politician and UK development minister. Key One people on board include Jamie Drummond, a long-standing advocate and campaigner, who founded the organisation with Bono; Lucy Matthew, Bono’s senior adviser; and Kathy McKiernan, his senior media adviser (and a former vice-president of Time Warner).

There are two journalists: Ellen McGirt, a US-based business magazine writer with an interest in entrepreneurs and development, and The Irish Times. Plus three people who look after Bono: Emma Pactus, Natalie Kinsella and Brian Murphy, his bodyguard.

Despite campaigning and touring for much of his adult life, Bono says that he still finds setting out on these journeys a wrench but that then, early on, there’s always an instant when his head clicks into gear.

“There’s always a moment,” he says, “a chiropractic moment when I know just exactly where I should be, and it’s here – here with [Drummond,] my partner founder, on this trip . . . You have no idea where these trips can go. You meet people and relationships start.”

Tuesday August 25th: Kigali, Rwanda

University Teaching Hospital of Kigali is a series of mainly single-storey buildings, with corrugated-metal roofs, spread across several acres near the centre of the Rwandan capital. Like the city, the hospital presents a face that is neat and tidy, well ordered and well maintained.

It is not a state-of-the-art, 21st-century healthcare facility but, with 565 beds and departments for surgery, pediatrics, oncology and maternity, plus a chronic disease unit, laboratories and a dispensary, it has the equipment, staff and medicines to cope with the 85 per cent of transfers that come from other medical facilities around Rwanda.

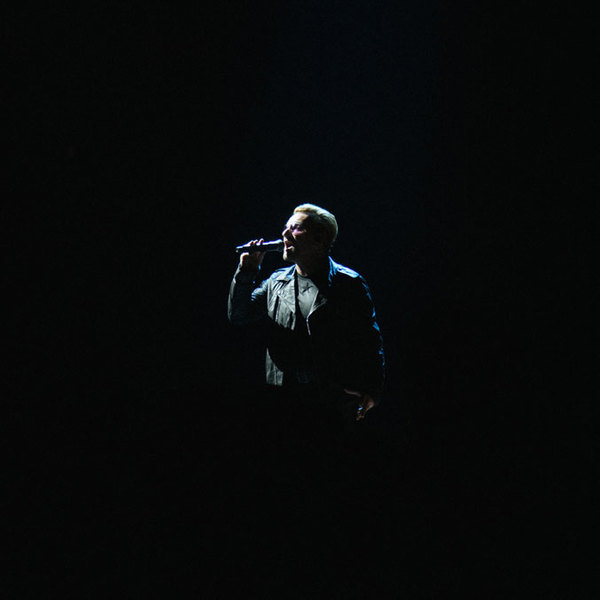

In one of the quadrangles created by a cluster of buildings a patio-style tent has been put up to give shade. On each side of the quad a row of chairs is filled by the visiting dignitaries. The centre is a big empty space.

Into it steps a young woman, hands clasped in front of her, head down at first, that mix of shyness and nervousness as she sways a little, left and right. She cuts a stunning figure: she is wearing an ankle-length cobalt-blue dress and a single gold chain around her neck. When she does look up her beauty is striking.

“My name is Anne,” she begins, “and I was 11 when I found I was HIV positive.”

Pause.

“I am 23 now.”

The message is simple, powerful and immediate. No one needs to spell it out: there is life after diagnosis; HIV doesn’t have to turn into full-blown Aids and death. All it takes is antiretroviral drugs.

Requesting that no photographs be taken or recording equipment used, Anne goes on to tell her story. It is a tale of how she wanted to fight to live and how she pursued her quest with a steely determination. Of how friends asked, in the early days after diagnosis, why she was always taking pills, the friends seeming to suggest that there was no hope. Why bother?

“I told them I wanted to live,” she says. “I wanted to live my dreams.”

She went to university and tells how now, living with HIV, as she puts it herself, “I walk and I hold my head high.”

There is applause and then silence as Anne’s triumph over adversity marinades in the emotions of her VIP audience.

Bono breaks the silence. Rising slowly from his chair, he asks Anne, “What did you study at university?”

“Finance,” Anne says with pride.

Bono snaps to attention, stands and salutes Anne. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he says, “I give you a future minister for finance of Rwanda.”