'This is the big sound," says the Edge. He rattles a basement rehearsal space with three monster chords from a vintage Epiphone Casino guitar, dunked in distortion so ferocious that his black baseball cap seems in danger of flying off. Bono is right beside him, listening hard, squinting at the fretwork through pale-blue aviator shades. The singer is wearing a hat of his own, a jaunty, black-banded Panama-style number that makes it look like he's in disguise, on holidays, or both.

No matter how huge a noise they make, U2 are, for once, playing in a little room. They've hauled an unreasonable amount of equipment and a half-dozen-plus crew members into a purple-carpeted, wood-walled studio at a TV station on the French Riviera, where Bono is leading them through rehearsals for radio and talk-show performances.

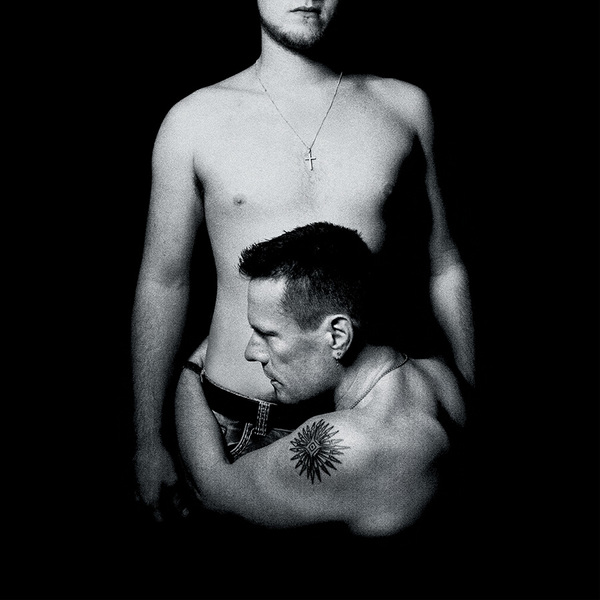

On this October evening, Larry Mullen Jr is at his drum kit, in head-to-toe black, running through a clickety-clacking song intro with uninterrupted intensity. Adam Clayton, in a sparkly purple shirt, bass guitar hanging at his waist, is flicking at his iPhone. He's probably checking his email rather than, say, looking for his free U2 album (or trying to delete it).

They're working up a live arrangement of their current single The Miracle (of Joey Ramone). The Edge's jagged "big sound" isn't quite working, even though it's exactly what he used on the version from their latest album, Songs of Innocence. "Songs are never finished," Bono says. Like almost all of their music, Miracle crawled out from a relentless process of forced, hot-house evolution - in this case, over four years, with three different producers. It started as a drum-loop-and-acoustic-guitar-based tune called Drummer Boy, from 2010 sessions with the producer Danger Mouse. Then it turned into a rock-ier larval-stage thing called Siren (one line compared the Ramones's music to a siren song) with heavy input from OneRepublic frontman Ryan Tedder and Adele producer Paul Epworth, before developing its definitive melody and lyric over two months of sessions with Epworth. But even now, it hasn't quite settled into a final shape.

"You've got a digital-sounding distortion," Bono tells the Edge. "It's not a sound that can lift. In the pre-chorus, is there a mezzanine level? You got a little brown sauce, so we need it more funky, more like Mysterious Ways. Try it with the Mysterious sound; see if it works." The Edge, stoic Spock to Bono's voluble Kirk, duly dials up that Achtung Baby track's wah-wah soup.

"All right, once more," Bono says, and Miracle shape-shifts once again, into something slinkier and more brash than the album version: Mullen overdelivers on Bono's request for "more cymbals, more dynamics"; Clayton nails what Bono describes as "a bass part so great you could build a house on it," with an occasional glance at a chord chart; Bono emotes at full concert volume into a hand-held mic, shaking his hips a bit, sounding implausibly youthful. "That was some numskull fuckin' business," says Bono. "Really good!"

As the Edge fiddles with his gear, Bono wanders over to offer some director's commentary. "We just need another colour," he says. "Because we're using a swing beat. Making this album, we went back and listened to all the music that had brought us into ourselves, then we said, 'Now let's misremember it.' The Ramones never used a swing beat in their lives - but the New York Dolls, they were glam: they did. People say, 'That song doesn't sound like the Ramones!' But that would not be a compliment, to pastiche them - we're trying to do something more interesting."

The Edge will stay here on his own for hours tonight, working out a new secondary sound and modified guitar part for the song, in hopes of "not going numskull all the way through." "The Mysterious Ways thing was the wrong idea," he'll say over breakfast the next morning, "but it led to the right idea."